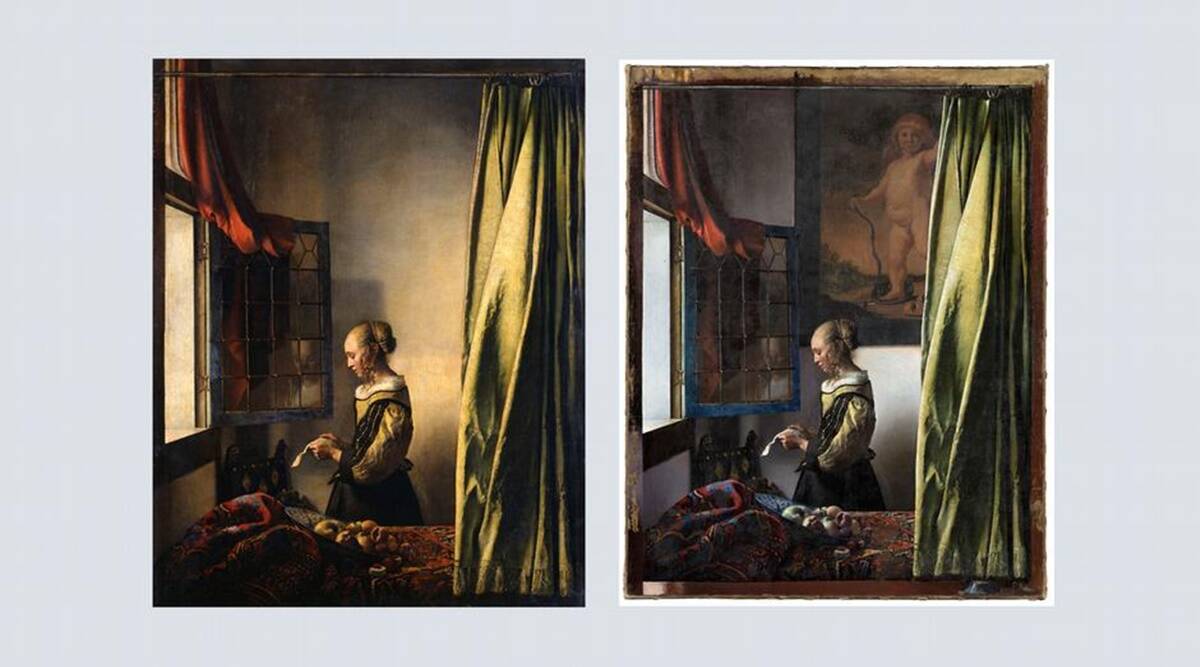

Experts of the Dresden State Art Collections were astonished when they closely examined Vermeer’s “Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window” using technical equipment: Under a layer of paint hid a youthful Cupid.

The artist had painted the figure on the wall behind the girl, who seems to be reading innocently. After two years of work to reveal the original, the painting was presented to a surprised audience.

Alongside Rembrandt and Rubens, Dutch painter Jan Vermeer (1632-1675) is considered one of the most famous artists of the Baroque period. His “Girl Reading a Letter” was and is considered one of the best works of the Dutch Golden Age between 1600 and 1700, during which the Netherlands prospered politically, commercially and culturally.

With only 37 paintings, Vermeer’s oeuvre is rather small, contributing to the excitement that the finding in Dresden triggered in the world.

The museum is now celebrating the painter with the exhibition “Johannes Vermeer. On Reflection.”

“Uncovering parts of paintings that have been drawn over is not always as meaningful as in the case of Vermeer,” says Maria Galen, expert for modern art and gallery owner in the western German city of Greven.

“Vermeer used the figure of cupid four times — as a ‘picture-in-picture,’” according to Uta Neidhardt, senior art conservator at the Dresden Museum.

Research and state-of-the-art laboratory tests have unambiguously confirmed that the love god, painted in brown and ochre tones, was covered up by a different hand that also covered up the amorous statement Vermeer originally wanted to make. But the case is not always this clear.

Searching for the perfect picture

What complicates the matter is the fact that pictures can be painted over in the most varied of ways.

Cologne’s Wallraf-Richartz Museum is currently holding an exhibition called “Revealed! Painting techniques from Martini to Monet.” A section of the exhibition engages with such artistic interventions.

“Painters have always sought the perfect picture,” says Iris Schaefer, chief art restorer at the museum. “There are only a few paintings, which are free of pentimenti,” she adds.

“Pentimenti,” the singular form of which is “pentimento,” essentially means the presence of images that have been painted over. This includes corrections, changes in motif and color, and even artistic interventions to the point of complete destruction of artworks.

But what drives artists to change their work? “There were many reasons for that,” Schaefer says. Sometimes artists had doubts regarding their self-worth, often actual life crises. Then again, criticism from observers, art dealers or buyers had consequences for the artwork.

But were “pentimenti,” or later changes in a painting by someone else, also executed to adjust the artwork to new moral ideals? According to Schaefer, it is not always easy to differentiate between the two.

In order to reveal the secrets of old paintings, restorers today use a growing arsenal of investigative methods. Even observing with the naked eye can reveal brush strokes which point to possible overpainting. Stereo microscopes allow 3D-vision with up to 90 times magnification. X-rays, infrared and ultraviolet rays seep into different depths of the picture’s surface and convey painting canvases or signature lines.

Art technologists at the Wallraf-Richartz Museum were astonished when they X-rayed “A Couple” by August Renoir (1841-1919).

Instead of the man and woman standing together at a park seen on the 1868 oil-on-canvas painting, the X-ray revealed a completely different image of two women sitting opposite to each other. “We thought we had pulled out the wrong painting from the developer fluid,” Schaefer remembers.

[“source=indianexpress”]