There is an anecdote narrated to me by the late Arun Jaitley that comes to mind on the day the final hurdles in the path of the construction of a grand temple to Lord Ram at his birthplace in Ayodhya have been removed.

The event centres on the evening of December 6, 1992, in the central office of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) on Ashoka Road in New Delhi. The news of the demolition had just come through. The party office was relatively deserted, with most of the party bigwigs either in Ayodhya or digesting the unexpected happenings in their homes. One of the few holding the fort was KR Malkani, a venerable intellectual who was also prone to believing in conspiracy theories. It was he, among others, who spun the story of the demolition being masterminded by a dirty tricks department of either a foreign power or the Congress government. The mood was sullen and confused.

At this point, in walked an exuberant Sikander Bakht, for long the most prominent Muslim face of the BJP. Without any inhibitions, he joyously embraced the veterans, called for mithai, and exclaimed loudly: Aaj to Hinduo ne kamaal kar diya (Today the Hindus have excelled themselves).

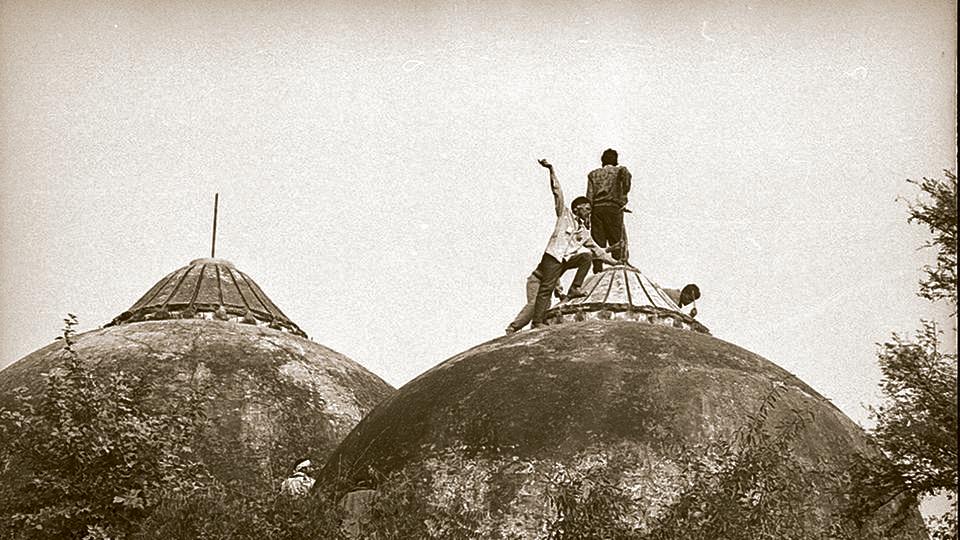

I was in Ayodhya that day, with LK Advani, Murli Manohar Joshi, Ashok Singhal, Uma Bharati and the entire leadership of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad. The scene was very different. As the demolition neared completion, the entire crowd swayed — as if mesmerised — to the ek dhakka aur do chant of Sadhvi Rithambara. As the final dome of the disputed Moghul shrine crumbled in a heap of red smoke, the mood was wildly ecstatic. Apart from Advani, who retreated into a dark room to reflect on the consequences of an unplanned deed, it almost seemed that the day of Hindu liberation had finally arrived.

Almost 27 years after the controversial demolition, an act which the Supreme Court has understandably held to be illegal, the construction of the Ram temple now seems assured. This was the moment of actual celebration, but as of now, the mood has been one of dignified restraint. Happiness has been coupled with an equal determination to not hurt the feelings of those who — quite erroneously in my view — equated the denial of a Ram temple with upholding the secular fabric of India. It was not merely India’s Muslims who were led to believe that the shrine built by Mir Baqi on a site venerated by local Hindus had come to epitomise India’s defence of minority rights. This was the consensual view of India’s cosmopolitan intelligentsia, who were bound by a common dread of Hindu assertiveness and, above all, the emergence of the political Hindu.

Denial has been the hallmark of the “secular” resistance. There was steadfast denial of the waves of temple destruction that had marked the history of India from the Sultanate to the death of Aurangzeb. Historians, some eminent and others charlatan, had been wheeled out by the score to inform Indians that popular narrative was spurious and that temple destruction, where it occurred, was not a sign of intolerance but assertions of State power. Undeniably, some of it was, but to those countless rural women I saw flocking to catch a glimpse of Advani’s rath yatra in 1990 and offering aarti, the re-construction of a temple in Ayodhya also meant securing justice at last.

This was something the leaders of the national movement had clearly understood and internalised. The reconstruction of the Somnath temple in the early 1950s was promoted and endorsed by nearly the entire post-Independence leadership, with the possible exception of Jawaharlal Nehru. It was seen as a symbolic act of redemption and an assertion of sovereignty after centuries of bondage. Unfortunately, the subsequent generation of politicians lost sight of this vision and took it upon themselves to equate national aspirations with prejudice and bigotry. It was this creeping polarisation that transformed Ayodhya into a national issue. It pitted ordinary decencies against an attempt to reinvent India.

When the Ram temple in Ayodhya is finally inaugurated, using bricks consecrated in countless villages and towns, it will signal the end of a long period of mental servitude and subordination. It should, hopefully, also mark an end to the long and bitter struggle to rectify the wrongs of history. What we are as a people has been shaped by history, but we cannot forever remain its prisoner. A final closure of the Ayodhya dispute will also mean looking ahead with the self-confidence of an unshackled people. There is a need for humility and even magnanimity. Equally, the sheer tenacity of the Ayodhya movement suggested a refusal to be cowed down by sneers and condescension. That determination should also be a guide for the future.

[“source=hindustantimes”]