Having recently been in Maranello to see the unveiling of the new Ferrari F1 racing car, I want to return to the automotive theme for this post, because a new chapter in the ~250-year history of the automobile is coming up. It’s a biggie in itself, but there’s also a security aspect of this new chapter that’s even bigger. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Time to engage reverse and go over this biggie first …

Of late, the headlines have been pretty interesting regarding the modern automobile — plus what one will look like in a few years to come. Examples: California will legalize the testing of self-driving cars on public roads, Swedish gravel trucks will load up, drive for miles and unload with no driver at the wheel, and KAMAZ has come up with a driverless electric mini-bus. Google, Yandex, Baidu, and who knows how many other companies from different spheres and countries are developing driverless projects. Of course, some of the headlines go against the grain, but they are mere exceptions, it seems.

And just recently I was at the food-processing plant of Barilla (our client, btw) in Italy and saw more automation than you can shake a spatula at: The automated conveyor delivers up tons of spaghetti; robots take it, package it, and place it into boxes; and driverless electric cars take it to and load it into trucks — which aren’t yet automated but soon will be …

So, self-controlled/self-driving vehicles are here already — in some places. Tomorrow, they’ll be everywhere. And without a trace of sarcasm, let me tell you that this is just awesome. Why? Because a transportation system based on self-driving vehicles that operate strictly according to a set of rules, has a little chance of degradation of productivity. Therefore, cars won’t just travel within the prescribed speed limits, they’ll do so faster, safely, comfortably, and, of course, automatically. At first there’ll be special roads for driverless vehicles only, but later entire cities, then countries, will be driverless. Can you imagine the prospects for the upgrade market for old driver-driven cars?

With that out the way, now comes the interesting bit — the reason for so many words in this here post. Let’s go!

Actually, I think we all understand how bright the driverless future is. Here, though, I’d like to look further than the horizon — and also under the hood. Automatic automobiles — that is, true automobiles — are just one aspect of the approaching industrial revolution. Everything becoming automated will affect the whole paradigm of personal transportation, including approaches to ownership and usage, associated standards, traffic rules, and, of course, cybersecurity.

“Smartmobiles” (a meme is born!) will create the biggest industrial network — V2X, or Vehicle to Everything — in the world. Through this network, smartmobiles will be able to communicate with one another to help each other out: If an ambulance is speeding along with its siren blaring, cars will get out of the way in good time so the ambulance can get to where it’s going and save people as fast as possible. Looking for a parking space (as well as the actual parking of the car) will become routine automation. Cars will warn each other about the need to brake for bumps or potholes in the road. Traffic jams will lessen because certain cars will be sent along alternative routes, and so on.

The development of driverless technologies and car sharing (CaaS — Car as a Service) could, within decades, turn the automotive world upside-down. Owning a car will become for many old-fashioned and unnecessary (for others it may remain a status symbol). But that’s natural when you see the alternative: When you can call up a car to arrive at your door when you want, with all personal settings already set up (music, seat position, temperature, etc.), to drive you along the optimal route in the shortest time — and when you don’t have to buy or service the car — the car will become a peripheral device for your mobile phone!

Indeed one could go on fantasizing on this theme for ages.

But I’ll now turn this discussion in a different direction — as you’ve probably guessed already, a cybersecurity direction…

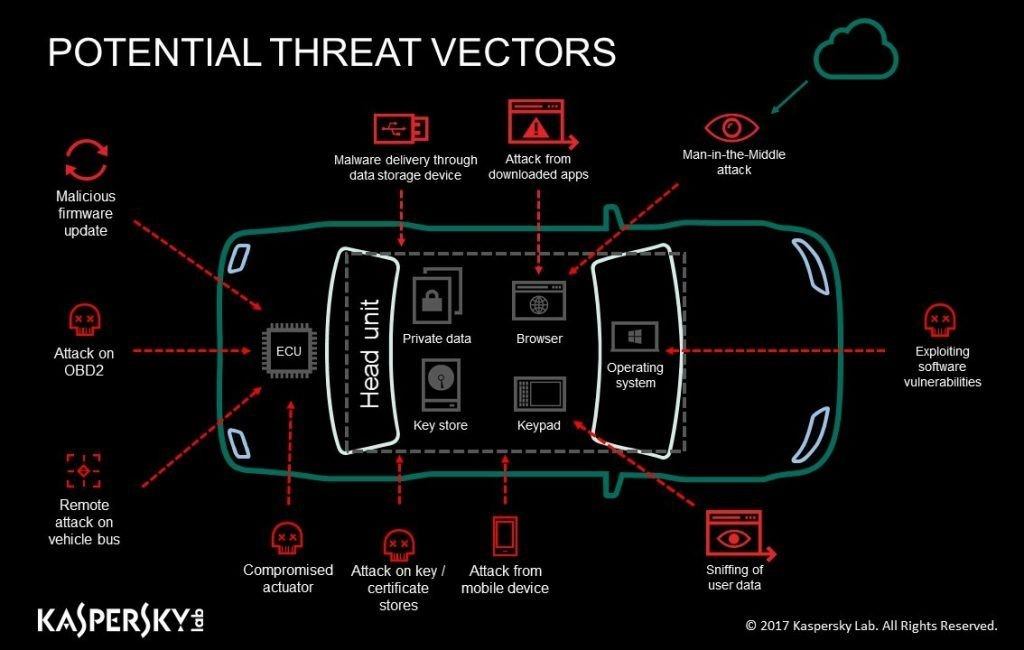

I’m sure that while reading this post, many among you will be thinking: “But it’s all unsecure!,” “it’ll be hacked before you know it!“, or even “there’s no way I’m getting in a car like that!” And you’d be right once, twice, even three times. Just look, for example, at the market for IoT devices: In the race for ever-improved functionality, manufacturers ignore security. But with IoT devices, cybersecurity negligence can lead to loss of data, privacy violations, and bricking of devices. With driverless cars, it can lead to loss of life.

Regarding the latter, at least car manufacturers understand this — and it’s why our cars still haven’t become fully “smart” yet. Manufacturers may make awesome kit, but cybersecurity isn’t their thing. Most carmakers limit themselves to “sandboxes” to isolate cars’ electronics — much like they do with applications in iOS. But to get totally effective and awesome protection there’s no way of getting round specialization — seeking out folks who do cybersecurity for a living — and who do it reeeaaally well.

But some manufacturers have shown some. I know of cases where a security researcher contacted a car manufacturer to offer his services to address a problem he’s identified, but the manufacturer says there’s no problem, thanks anyway. So the researcher demonstrates a few simple scenarios leading to a total hack of the computer system of a — while it’s moving (!!), from the car running beside it (!!!). Only then does the manufacturer take the researcher seriously. But this is the way it is with security of so-called smart cars: it’s so weak as to be a gift to hackers:

So — yeah, you get it. To have superior cybersecurity for smart cars, manufacturers need to work with others. Some understand this, which is encouraging, but some go one further and work with others on joint development of technologies to come up with real solutions. One example: our joint project with AVL to create the Secure Communication Unit (SCU)), which protects communications between car components and the computer that’s controlling them all.

In simple terms, the SCU is a module controlled by our Secure OS that protects a car from hackers and malware. In it are several interesting patented inventions (three patent applications in the U.S. (US16/120,762; US16/058,469; US16/005,158), and three in Europe (EP18194672.4, EP18199533.3, EP18182892.2)), which cover a special gateway that gets embedded in the computer system of the car. The gateway analyzes data about the operation of the electronic blocks and also network activity, and indicates any anomalies it finds that could be a sign of a cyberattack, unsanctioned intervention, or technical fault. The analysis uses a database of rules that describe different attack scenarios, plus plenty of machine-learning technologies. So, in short, it’s a smart hardware filter customized for smart cars.

The filtration rules are developed together with the automaker, and if the rules are triggered the gateway can block dangerous actions and send a notification to the owner. Thus, should the Miller-Valasek hack have been attempted on a protected car, it simply wouldn’t have worked — and Fiat Chrysler wouldn’t have had to recall 1.4 million Jeeps! (I can’t begin to think how much financial and reputational damage that did to the company.)

There’s more: Just supposing a sophisticated cyberattack were to get around our protection (there’s no such thing as 100% protection, remember?), the manufacturer would be able — within hours, or a day, tops — to quickly patch the vulnerability via the SCU, without needing to wait for a new patch for the car. And such quick application of a solution on all vulnerable cars — remotely, from Alaska to Zimbabwe — is almost as important as the initial protection which should not normally even be gotten around.

I mentioned use of machine learning. Well, it’s constantly going on in the background, taking note of the telemetry in the electronic blocks and analyzing it with machine-learning algorithms in the cloud to uncover unknown cyberattacks. But there’s a bonus — actually, several: This journal can be used as a recorder of events for wider application. For example, folks buying used cars will be able to look at the true “medical history” of a car. Or, in case of a crash, drivers will have evidence of what really happened. Car parts being replaced and repair works can be monitored too, and so on and so forth. In a nutshell, it’s always nice knowing what’s happened under the hood of your car.

Skeptics might ask what happens if a bad actor rips out the SCU and reprograms it. After all, mileage tampering still happens. Come on, please. We’re a cybersecurity company! That’s the first thing we thought about. Tampering with the SCU is simply impossible given the secure architecture.

Mathematical proof:

Data is signed with technology that’s in some ways similar to blockchain: Each new block of data is encrypted with a key with dynamic metablocks (date, time, etc.) and hereditary characteristics from the signatures and key of the previous block. In the simplest arrangement, restoring the chain of keys is possible only with knowledge of the very first key, which is generated by a trusted “black box” and installed by the automaker. In other words, it guarantees the authenticity of data, and that data can be used, for example, for monitoring manufacturer guarantee conditions, ecology readings, or the sleep and rest of professional drivers, or for calculating insurance premiums on the basis of how well a driver drives. The data it collects could even be used as evidence in court.

So, you see, we’re big into automotive security. However, it’s not only protecting vehicles into which we’ve diversified in recent years. In fact, no other traditional competitor of ours has gone so deep into solutions outside traditional antivirus. We protect critical infrastructure, embedded systems, and IoT, and provide a wide range of threat intelligence services — and that’s in addition to our own secure OS, mentioned above, which, by the way, isn’t a mere cosmetic adaptation of a desktop antivirus (like … hmmm … best not point fingers:) but a specialized technology that we created from the ground up with specific spheres of application in mind. No wonder this market is growing faster than any for us: In 2018, our non-endpoint sales rose 55%. Indeed, I’m sure that the future lies in creating scalable, multidimensional ecosystems of cybersecurity technologies for building a truly cybersecure world, ecosystems that will move us from the paradigm of cybersecurity to one of “cyberimmunity,” treating the causes, not the symptoms.

[“source=kaspersky”]